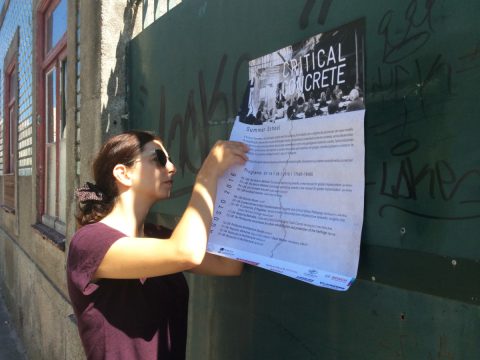

Critical Concrete

December, 2015-March, 2018

(Porto, PT)

Critical Concrete is a Porto-based educational and socio-cultural initiative that revolves around sustainable architecture. It was founded in 2015 by Samuel Kalika and started with a summer school that brought together families-in-need, students and an interdisciplinary group of mentors, researchers and practitioners to refurbish various buildings with a social interest. Since its beginnings, Critical Concrete has developed its activities towards research in sustainable architecture – including sustainable materials and practices. It also consists of a work and event space, where it hosts workshops on socially-engaged architectural experimentation but also cultural events, such as film screenings, markets, etc.

Critical Concrete emerged from the founder’s personal experiences of living and working in Berlin for an artist-run organisation that claimed to foster socially engaged art. After several years living in a sublet flat and increasing difficulties to sustain a living while also considering the art projects he administered failing to become socially relevant, he decided to start his own project space.

For this, he decided to move to Porto, a secondary city in Portugal whose economic situation would still give him space for experimentation.

When he searched for a house to host his project, Samuel came across the issue of social housing.

“First my move to Porto was to develop this future place...

..and then the social housing thing appeared.

There is this specially characteristic housing configuration in Porto, which is called Ilhas, which means island. Basically, these islands are very small habitational units, like from 15 to 20 m2 each […] normally the kitchen is in the small house unit, but common bathroom and common garden. I saw this place and I thought it is really cheap… [but] if I had bought this place, I would have become suddenly a landowner, trying to get his rent. I really did not want to do that. It is not like an occupation I found really fun. I discarded the idea, but then thinking about it as a project in a sense, because people were living in conditions that are unbearable – all the mould in the house, really terrible – and the only interesting thing would be to transform this place into what it is: a functioning social housing configuration… Actually, from this place, from which nothing happened, came the idea of Critical Concrete. (Interview, 15 December 2015)”

He planned to set up a three-week summer school during which international students, mainly from architecture, design, engineering and related subjects refurbish one social housing configuration, gaining practical knowledge on materials, tools, and finding solutions for real demands, while supporting local families in need.

Together with Juliana Trentin – his collaborator he met on the way – they eventually found a former community building that was important to the neighbourhood. It had taken on various functions over the last years from a kindergarden to a venue where scouts met but all those initiatives did not have the resources for the much-needed maintenance work.

The idea was not only to make it the headquarter of Critical Concrete but to develop the building into a production centre in which co-working and co-building facilities were open to the local and an international community interested in ideas and techniques of sustainable and repairable production processes.

In order to be able to set up a summer school that serves educational purposes as well as serving the local community by refurbishing socially relevant places with little money, Samuel and Juliana started collaborating with the local authorities to find suitable places. Focusing on social housing configurations, the Critical Concrete team-members were aware that they were dealing with individuals ‘in very vulnerable situations’ structured by profound inequality.

In order to enable the students to act from a position of citizens with expertise operating from within the community, Samuel and Juliana very carefully crafted the relationships between the various participants to counter unequal structures.

For instance, they refrain from telling the house owner’s personal story of fate when introducing the house they plan to refurbish. Instead, they acknowledge house owners as the ones who provide the ‘worksite’ for Critical Concrete’s sustainable, alternative and socially-engaged architectural experiments and materials. As such, the houses are professional (architectural) challenges linked to the history of the city and situated in challenging legal and socio-economic contexts.

Students, mentors as well as the owners of socially relevant places, their families and other stakeholders negotiate and participate in the refurbishment at different stages. Media coverage, instead, serves distributing these alternative ways of developing the urban environment, thereby criticising conventional ways of city development schemes that more often than not compartmentalise heterogeneous and complex urban cohabitation into homogenous districts and units and turn homes into real estate.

Since the first summer school in 2016 Critical Concrete has turned into a hub for various people interested in sustainable, experimental, participatory and critical formats of architecture and urban development intersecting local and international communities.

In its ongoing search for affordable and long-lasting alternatives to conventional construction techniques it has also developed into a research unit with expertise in renewable, repairable and sustainable building materials.