1) Creed, M. (2005) If you’re lonely. Accessed 12th April 2016 at: http://www.martincreed.com/site/words/if-youre-lonely.

2) Arendt, H. (1981/2016) Vita activa oder Vom tätigen Leben, p. 16. München: Pieper.

3) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.109. Durham: Duke University Press.

4) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.2. Durham: Duke University Press.

5) Marx, K. (1863/n.d.) Theorien über den Mehrwert, MEW 26.3, p.300.

6) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.52. Durham: Duke University Press.

7) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.3. Durham: Duke University Press.

8) Gielen, P. (2009) The murmuring of the artist multitude: Global Art, Memory and Post-Fordism, p.23.Valiz, Amsterdam.

9) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.4. Durham: Duke University Press.

10) Gielen, P. (2009) The murmuring of the artist multitude: Global Art, Memory and Post-Fordism, p.24.Valiz, Amsterdam.

11) Engels, F. (1844/1976) “Umrisse zu einer Kritik der Nationalökonomie”, p.524, in: Karl Marx/ Friedrich Engels – Werke, pp. 499-524. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

12) Shukaitis, S. (2016) The composition of movements to come. Aesthetics and cultural labour after the avant-garde, p.177. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

13) Gielen, P. (2009) The murmuring of the artist multitude: Global Art, Memory and Post-Fordism, p.24.Valiz, Amsterdam.

14) Creed, M. (2005) If you’re lonely. Accessed 12th April 2016 at: http://www.martincreed.com/site/words/if-youre-lonely.

15) Gielen, P. (2009) The murmuring of the artist multitude: Global Art, Memory and Post-Fordism, p.19.Valiz, Amsterdam.

16) Bücher, K. (1899) Arbeit und Rhythmus, p. 2. Leipzig: Teubner.

17) Fisher, M. (2014) “What is it you’d say you do here? The Post-Fordist compedy of management”, p.70 in: N. Möntmann (ed.) Brave new work. A reader on Harun Farocki’s film A New Product. Köln: Walter König.

18) Shukaitis, S. (2016) The composition of movements to come. Aesthetics and cultural labour after the avant-garde, p.68. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

19) Fisher, M. (2014) “What is it you’d say you do here? The Post-Fordist compedy of management”, p.66, in: N. Möntmann (ed.) Brave new work. A reader on Harun Farocki’s film A New Product. Köln: Walter König.

20) Creed, M. (2005) If you’re lonely. Accessed 12th April 2016 at: http://www.martincreed.com/site/words/if-youre-lonely.

21) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.46. Durham: Duke University Press.

22) Shukaitis, S. (2016) The composition of movements to come. Aesthetics and cultural labour after the avant-garde, p.70. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

23) Shukaitis, S. (2016) The composition of movements to come. Aesthetics and cultural labour after the avant-garde, p.71. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

24) Hardt, M. & Negri, A. (2011) Commonwealth, p. 151. Belknap Press.

25) Duchamp, M. /Cabanne, P. (1971) Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, p.72. London: Thames and Hudson.

26) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.43. Durham: Duke University Press.

27) Hardt, M. & Negri, A. (2011) Commonwealth, p. 153. Belknap Press.

28) Weeks, K. (2011) The problem with work. Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries, p.97. Durham: Duke University Press.

29) Foucault, M. (1976) “Die Macht und die Norm”, in ders. Mikrophysik der Macht, p.117. Berlin: Merve.

30) Power, N. (2014) The social brain an its missing body. Work in the age of semio-capital”, p.95, in: N. Möntmann (ed.) Brave new work. A reader on Harun Farocki’s film A New Product. Köln: Walter König.

31) Arendt, H. (1981/2016) Vita activa oder Vom tätigen Leben, p. 16. München: Pieper.

32) Creed, M. (2005) If you’re lonely. Accessed 12th April 2016 at: http://www.martincreed.com/site/words/if-youre-lonely.

Category: Uncategorized

Working Utopias

I hope work as a relation is friendship.

I hope work as a relation becomes less dominated by fear.

I hope work as a relation is trying again.

I worry that work relations become increasingly strategic.

I worry work relations are undermined by competition.

I hope that work relations can be structured differently than merely through market logic.

I hope work as a relation is collective daydreaming.

I worry about the strategic cruelty of professionals.

I wonder what parasites do to work relations.

I worry that work as a relation is defined by efficiency.

I hope work as a relation can transgress networking logics.

I hope we start building packs.

I hope work as a relation is based on trust.

I worry that work as a relation is dominated by opportunism.

I hope that work as a relation is making space for togetherness.

I hope work as a relation has more time to unfold.

I hope that work as a relation can balance fears.

I worry about how much is excluded in current work relations.

I hope that decision-making is shared in work-relations.

I worry about abusive work relations.

I wonder what complicity does to work relations.

I worry that work as a relation is affected by opportunistic strategies.

I worry that work as a relation is affected by an increasing unequal distribution of resources.

I hope that work as a relation embraces the unpredictable.

I hope that work as a relation gives shelter for the not yet fully grown, not fully developed ideas, desires, plans and people.

I hope that work as a relation can also handle deals.

I hope that work as a relation can recuperate patience again.

I worry that work as a relation is overpowered by expectations.

I worry that work as a relation has been replaced by functions and positions.

I hope we can work side by side.

I hope that work as a relation gives more space to everyone.

I worry that intimacy can be abused in work relations.

I hope that we do not lose respect for the other.

I hope work as a relation nurtures solidarity.

I hope that work as a relation is growing.

I wonder how to think about the future of work relations.

I hope that work as a relation gives enough time for listening.

I hope that work as a relation leads to joint forces.

I hope work as a relation invites [ex]change.

I hope work as a relation becomes more caring.

I hope we can also let go of work relations.

I hope.

Hope as being committed to a proposal as a practice of respect.

Hope as listening.

Hope as witchcraft that names and invites those who are missing.

Hope as a sensing and working with different energy levels.

Hope as a practice to unfold something powerful.

Hope as picking up and joining ideas of different people as a practice of mutual engagement.

Hope as sharing worries, dreams and personal longings as a practice of trust.

Hope as awareness of the importance of protecting, nourishing and letting the inside grow to open up to the outside.

Hope as a being open and curious towards others as a practice of being non-judgemental.

Hope as acknowledging the fragility of embryonic encounters as a practice of protecting.

Hope as making space despite fear.

Hope as a practice of spacing.

Hope as a practice of bricolage.

Hope as exploring the threshold that in- and excludes instead of reproducing it.

Hope as rejecting the power of the factual.

Hope as dancing as a practice of togetherness, that does not need words.

Hope as focussing on interest and fascination instead of achievement and expertise.

Hope as a practice of rendering the unknown as a lateral presence that does not give answers but determines action.

Hope as experimenting with transgressing the own boundaries as a practice of taking risks.

Hope as being prepared to be disappointed.

Hope as remaining prepared to be affected to affect.

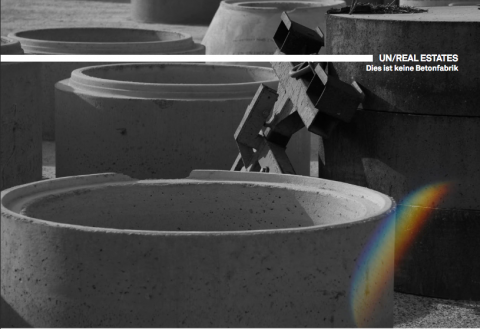

Dokumentation Un/Real Estates: Dies ist keine Betonfabrik

The full documentation can be found here

Networks in space and time – Activating Gaze, Imagination and Senses of Space in and for Stolpe

The workshop lasted 3 hours and consisted of four exercises, all of them are used in contemporary dance. They come from artists/movers who aimed at finding new approaches to movement in the 60’s and 70’s. Since then these approaches were further developed from generations of dance and movement practitioners. All of them aim at activating different sensory perceptions, for instance the gaze, the touch and also to a certain extent our kinaesthetic sense.

We wanted the students to explore the location ”Betonwerk Stolpe” physically by moving in space. The focus was to be attentive to the sensations of the own body in relation to the others and in relation to the space – and to raise the awareness in which way the body is directly influenced by the environment.

Whilst the first exercise was moving and aiming at making eye-contact to explore the space that opens up and develops along the connection of the gaze between two people, for the second exercise we asked half of the students to move in space with their eyes closed. We asked the other half of the students to guard the blind and varied the ways they did so – starting with touching the blind partner, then not touching but intervening only if the blind partner is ‘in trouble’ and eventually asking them to change the guard without letting their partners know. After these exercises, we came together to reflect on experiences made so far with everyone.

The second part of the workshop consisted of two parts. For the first part, we asked the students to pair up, go out and “observe what needs to be observed”. When they came back after half an hour, we asked them to share these explorations with each other in movement, using as little words as possible. Although the students felt a little uncomfortable in this last task, everybody took the courage and joined in. Usually working with performance art and dance students, we were surprised how fast these exercises pushed the students out of their comfort zone and we were even more impressed of their curiosity, openness and how much courage they had following us regardless.

For us, it was a fascinating journey to see how these students from different departments, different cultural backgrounds, who hardly knew one another came closer through connecting with their bodies and senses. At the same time as they connected with one another, their widened sensual awareness also made the physical and atmospheric dimension of the Betonwerk more tangible. To observe how careful the students were with one another and the care with which they started exploring the physical space was for us like to listen, to sense, to be attentive and responsive to what is present, although at times invisible, to affect and to be affected.

Reconceptualising Solidarity in the Social Factory: Cultural work between economic needs and political desires

Notions of formal and waged employment still dominate current conceptualisations of work-related solidarity. This article argues that it is increasingly difficult to distinguish between work and non-work. Considering cultural production as laboratory for new forms of work, this article uses Hannah Arendt’s distinction of labour, work and action to explore a cultural project that negotiates conflicting economic and political demands. It identifies solidarity as temporary phenomenon that draws together disparate groups and that necessitates constant engagement to create and maintain its conditions. Work aiming at solidary action, however, cannot be analysed without considering labour that sustains the needs of the individuals involved. Yet, when being subjected to individual economic needs, the solidary action can be compromised.

Abstract

Notions of formal and waged employment still dominate current conceptualisations of work-related solidarity. This article argues that it is increasingly difficult to distinguish between work and non-work. Considering cultural production as laboratory for new forms of work, this article uses Hannah Arendt’s distinction of labour, work and action to explore a cultural project that negotiates conflicting economic and political demands. It identifies solidarity as temporary phenomenon that draws together disparate groups and that necessitates constant engagement to create and maintain its conditions. Work aiming at solidary action, however, cannot be analysed without considering labour that sustains the needs of the individuals involved. Yet, when being subjected to individual economic needs, the solidary action can be compromised.

Introduction

Classical conceptualisations of solidarity, such as those by Hegel, Marx or Durkheim have closely been linked to work (Smith, 2015) and seen in light of an on-going political struggle between the working class and the bourgeoisie. This ultimately leads to conceptualisations of solidarity as a form of connection or association between workers, informing studies in terms of unionized solidarity (Hyman, 1999, 2015). In recent decades, however, work has undergone a global shift in nature in recent decades mirrored in a growing discussion about various types of work that considerably differ from standard employment.

Contributions engage with informal employment (Visser, 2017), contingent work (Bolton and Laaser, 2013), un-paid work (Siebert and Wilson, 2013) or pose the more fundamental question of what is work after all (Kirton, 2013). The latter points out that the numerous processes of creating and maintaining distinctions between different categories of work and non-work should become central points of interrogation (Hatton, 2015). With forms of non-work starting to display the same form of productivity (Virno, 2004; Hesmondhalgh, 2010; Terranova, 2000), capitalist forms of exploitation have long left the boundaries of the workplace and become relevant to the process of capital accumulation in what Tronti (1966) coined ‘social factory’ (van Dyk, 2018; Weeks, 2011). This dwindling of standard employment is also reflected in re-considerations of work-related forms of solidarity that have traditionally been associated with organized labour (Hyman, 2015, 1999). Discussions on ways of revitalising unions, for instance through strategies of organising (Engeman, 2015; Connolly et al., 2017), suggest that currently these forms of solidary, too, are subject to change. Central in these debates, however, remains a concept of work as waged activity combined with notions of community and membership. Such emphasis on community or even homogeneity (Bayertz, 1999), however, tends to fall short of grasping possibilities for solidarity in light of precarious labour conditions, increasing mobility, flexibility and consumerism contributing to ever-growing individualisation (see, e.g., Virno, 2004). Within this setting, cultural and creative workers symbolise ‘more than any other […] transformations of work’ (Gill and Pratt, 2008: 2). Not only because a considerable part of their labour being non-waged (Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2011; Hesmondhalgh, 2010), but also because the value they created is often siphoned off by others, for instance, the real estate industries. Although highly visible in the discourse on immaterial labour and precariousness (Sholette, 2011), cultural workers have not managed to mobilise and formalise solidary action. Often, creative workers’ individualistic subjectivities are considered to block collectivity from emerging (Shukaitis and Figiel, 2015), because striving for ‘creative autonomy’ is assumed to compete with pursuing solidary action (Umney and Kretsos, 2014: 586). In contrast to this assertion, this article assumes that the very characteristics of cultural work as being transient, precarious and individualistic make it ideal to reconsider and extend the discussion on work-related solidarity. While not intending to diminish the importance of unions as political leverage to negotiate social injustice, this article, thus, introduces a case study of an artist setting up a project that addresses the issue of social housing to explore how solidarity may be contained and enacted ‘in creative work itself’. Cultural work is ridden with conflicting logics that oscillate between commercial, artistic and political imperatives (Eikhof and Haunschild, 2007).Drawing on Hannah Arendt’s (1958/1998) distinction between labour, work and action as well as her understanding of solidarity as action in the public sphere, this article explores cultural work’s potential for solidarity under these conditions, thereby contributing to the nascent discussions on changing notions of solidarity within changing concepts of work. It does so first, by situating the study in current discussions on work to point out gaps with regard to how work and related notions of solidarity are conceptualised. It then introduces Arendt’s distinction between labour, work and action as analytical framework for carrying out a close analysis of a cultural project with an explicit political intent to address the mechanisms of value-production and extraction beyond waged-work. The analysis shows that in contrast to institutionalised forms of organised labour, solidarity in the social factory it not linked to notions of stable community or homogeneity but a temporary phenomenon between ever-changing actors who need to actively create the conditions for it. This article shows that solidarity as a political concept is always precarious in that it is always prone to co-option and exploitation. A critical discussion of the findings links the analysis to debates on possibilities and the ambiguities of solidary action within contemporary forms of work.

Human plurality […] has the twofold character of equality and distinction. If men [sic!] were not equal, they could neither understand each other […] …

Arendt, 1958/1998: 175–176

Solidarity and changing forms of work: the case of cultural labour

Solidarity is generally seen as mediating between the individual and the collective (Scholz, 2015) and bridging different interests (Banting and Kymlicka, 2017). Related to work, it often appears as an institutionalised and formalised set of practices involved with formal employment. Solidarity between workers is assumed ‘because they are workers’ (Simms, 2012: 113, emphasis in original), which conjures up an image of homogeneity. Considering that ‘solidarity is always an achievement, the result of active struggle to construct the universal on the basis of particulars/differences’ (Mohanty, 2003: 7), such a homogeneity cannot be assumed per se, in particular not for cultural workers. Work in the cultural sphere is subject to various ideological and structural constraints that undermine homogeneity even if cultural workers are represented by a union, such as actors (Dean, 2012).

Umney and Kretsos(2014: 573), for instance, argue that the very ‘bohemian appeal of creative work as a means of evading the capitalist labour process’ undermines the strength needed to act in solidarity on the labour market. At the same time, income is closely linked to individual reputation (stardom), so that ‘solidaristic concepts like established minimum rates are likely to be weakened’ (Umney and Kretsos, 2014: 586). Against Coulson (2012) who highlights the communitarian, non-utilitarian activities of creative workers and sees a possibility for solidary action within the cultural sphere, Umney and Kretsos (2014) state that this over-romanticises cultural work and instead point to the often flawed and cliquish character of entrepreneurial networking that cultural labourers pursue. While the discussion so far emphasises on solidarity as a form of collective action, cultural workers often engage individually with the politics of their working condition (Eikhof and Haunschild, 2007), for instance by making them content of their cultural production. Avant-garde artistic production, for example, has always been highly involved with politics, which is reflected in debates around framing political art as activism or considering politics being constitutive of art production (Bishop, 2012; Kester, 2011). Shukaitis (2016) points out the specific connection art has to labour politics that is mirrored in the way artists critically respond to processes of commodification through their art production, for instance, by responding to the market’s crave for art objects with more ephemeral formats, such as fluxus art, relational aesthetics (Bourriaud, 2002), participatroy art (Bishop, 2012) or socially-engaged practices. The political potential of such artistic responses, however, is often debated when being fed back into commodification and marketisation processes that also allow artists to make a living from their art. As a starting point, this article takes the need of cultural workers to negotiate conflicting demands, such as commerce and creativity (Eikhof and Haunschild, 2007) and extends it with regard to the political to explore how solidarity may be contained and enacted ‘in creative work itself’. Moreover, the specificities of cultural work also entail that a narrow focus on formalised employment that still dominates an engagement with work-related solidarity must be put into question. Tronti’s (1966) term of the ‘social factory’ helps to expand the analysis of value production within today’s circuits of capitalism (Böhm and Land, 2012). The social factory is characterised by the operation of interlocking systems of exploitation that draw together apparently unconnected phenomena for which cultural work is exemplary. Shukaitis (2016), for instance, refers to the discourse of the Creative Class (Florida, 2002) that at once reconceptualises creative labour as a form of personal fulfilment (McRobbie, 2016), which leads to a labour force that works longer, harder and for less pay (Hesmondhalgh, 2010), while using cultural initiatives for neighbourhood renewal to reinvigorate capital accumulation based on land value. These seemingly disparate aspects contribute to value-production beyond the immediate sphere of work and is siphoned off by other actors, such as the real estate industry. At the same time, they aggravate not only the situation for everyone marginalised in capitalist value-production – unemployed, old, young, unpaid house-workers, etc. – but also cultural producers who are at the heart of it. Hence, working ‘in’ the social factory does not necessarily produce a homogenous group of workers but bears potential of forming ‘a multi-class precariat’ (Ross, 2008: 34) that asks for work-related solidary action beyond the workplace.

Beyond the realm of employment, solidary relationships are conceptualised as occupying a middle ground in between ‘anti-social egocentrism’ and ‘one-sided “thou-centrism” such as altruism, sympathy, caring, or Christian charity’ (Laitinen and Pessi, 2015: 2). Connected to this is a concept of reciprocity that goes ‘beyond the duality of giving, receiving and the obligation to give in return, to exchanges across and between different subgroups’ (Sahakian, 2016: 210) which makes interdependence voluntary and based on interestin community (Servet, 2009) without community being presumed. This resonates with Arendt’s (1958/1998) political concept of solidarity that can only be enacted in the public sphere, which differs from the social sphere in that the latter is marked by an ‘assumed one interest of society as a whole in economics’ (p.40). The public, instead, is characterised by plurality that is, commonality situated in difference.

… If men were not distinct […] they would need neither speech nor action to make themselves understood. Signs and sound to communicate immediate, identical needs and wants would be enough.

Arendt, 1958/1998: 175–176